The Pumpkin and the Nation

1861 to 1899In the late nineteenth century, raising pumpkins was antithetical to all the new trends in American agriculture. The mode and scale of its production—hand picking a few acres—were anachronistic. “It is about time that pumpkins were retired from service and entered upon the fossil list,” wrote the influential journal The Horticulturalist in 1870. Yet the pumpkin, one of the least profitable and palatable of vegetables, appeared regularly in the popularly Harper's Weekly; it was a star attraction at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair; and it became the celebratory finale of Thanksgiving, the new national holiday that rivaled the Fourth of July even then. Americans celebrated the pumpkin for the very reason that made it a “fossil” in the world of agriculture – its associations with an old-fashioned way to make a living off the land. As Americans erected more skyscrapers, laid more railroad tracts, and pursued greater wealth and material goods with diligence, many felt they were losing their connection to the natural world, an authentic way of life, and their cultural roots. The pumpkin helped them rebuild those connections.

|

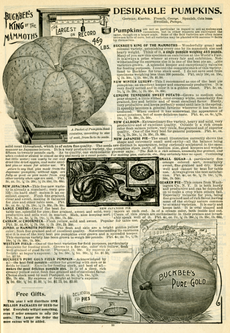

Changing Name and Face of PumpkinsThe pumpkin’s cultural affiliations with an idyllic small family farm, not its practical uses, spurred the innovation of new names and varieties, such as Burpee’s Golden Marrow and Buckbee’s Pure Gold.

|

Jack-O'-Lantern

|

Good Pie

|

Desirable Pumpkins

|