From Pumpkin Beer to Pumpkin Pie

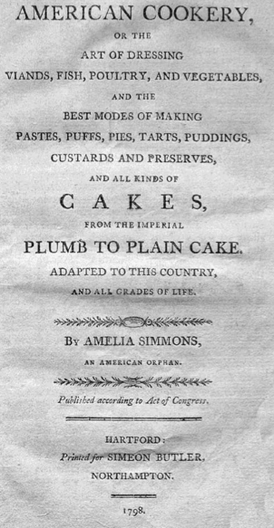

1600 to 1799American Indians introduced the pumpkin to Europeans who regarded it with the same mix of wonder and disdain that they viewed much of North America. While “squash” is a derivation of the Algonquian askutasquash, the name pumpkin is a derivation of the French pompion, which comes from the Latin pepo, meaning to ripen. Before Europeans encountered American varieties of pumpkins and squashes, a pompion connoted to them a large fruit or melon. This fact helps explains why some illustrations of American pumpkins from the era resemble melons more than they do pumpkins. While the Pilgrims might have eaten pumpkins at their famous 1621 Thanksgiving (though there is no record of them serving it), they probably ate them the day before and the day after, too. Because it was inexpensive to produce, grew like a weed, and was durable and versatile as a foodstuff, colonial Americans made pumpkin daily fare, similar to how Americans eat baked squash today. When they had no apples for pies, barley for beer, or meat for supper, they could substitute the prolific pumpkin. Yet they were happy to switch to European products as soon as they could.

|

Changing Name and Face of PumpkinsEuropeans initially referred to squashes and pumpkins as melons or cucumbers, which were familiar to them as African imports and similar in physical properties to the native American crops.

|

Europeans Compare Pumpkins to Melons

|

Europeans Make Pumpkin a Totem of North America

|

Americans Make Pumpkin Their Own

|